One thing that really stands out about indie games is the plethora of non-traditional games. I don’t just mean in terms of mechanics, but experiences. I know someone’s going to shout about “social justice warriors,” but I’m betting many of those same people choose female avatars when given the option or even main a female fighter in a fighting game. I’m not here to put down any position, but rather praise games that push the boundaries in new, interesting ways, not just in terms of race and gender, but perspective, and IndieCade 2017 had a lot of diversity experiences beyond simulated dystopian futures.

Bury Me, My Love

Bury Me gets its title from an Arabic saying that means something like, “Please don’t die before me.” Your partner, Nour, is escaping the country while you stay behind to take care of family. The only thing you can do to help her is encouraging her via a “What’s App” like text messenger, which is the basis of the game. Nour will ask for your help and respond in real time. That is, if Nour says she needs to run errands, she’ll disappear for a few hours and you’ll simply have to wait to hear from her again to continue the game.

It’s an interesting idea and unlike a lot of mobile games, isn’t a game of timers because you didn’t spend $X to speed up a mission, you’re waiting for someone to live their life, similar to how if you text someone with a job, they can’t always get back to you right away. Mechanically, it’s a choose your adventure story except, well, you’re choosing your partner’s adventure.

The characters feel real in that they’re imperfect. You’ll be blamed for things you have no control over simply because someone’s stressed out, personalities will clash, and you won’t be able to buy/shoot your way to glory but rely on social skills. The devs researched their work and got feedback from real refugees to make sure the story wasn’t just appropriate but realistic.

As someone from a mixed family with Arabic speaking roots, I can relate to the social unrest in places you’d think would be immune to such upheavals. Cultural practices, greetings, and places I understand, however, may overwhelm people not familiar with that part of the world. I remember playing Age of Wushu during beta and being overwhelmed with Chinese names, words, and places littering the game world with little to no context, which ultimately led to giving the game up. I don’t think Bury Me, My Love goes that far, assuming you at least know some geography and simple phrases, but I can imagine it being similar for some audiences. A few more pictures with labels showing you explicitly just a city with a “strange” name could help invite more players to embrace the story.

Everything is Going to be OK

Less of a game than an, “interactive ‘zine” ranging from “click the thing” to “choose your own adventure,” Everything is Going to be OK seems simply like random humor and bad Paint art at first blush. There’s over 20 “episodes” with various lengths, but all seem to share the idea of persisting even when things look bleak, from a bunny diving to it’s death by spears at the bottom of a cliff to a seemingly endless survey someone somehow got stuck in.

I won’t lie, the art and non-sequitur humor can be off-putting, but digging a little deeper reveals some oddly reflective thought. For example, the bunny plunging to its death is absurdly upbeat. Its death is certain but, well, it lives, and falls repeatedly. At the end of the short, after having the bunny bounce around its pointy landing spot, I could choose if this was “good” or “bad.” I chose bad and noticed episode 11 came to the front. That episode had a bunny impaled on one of those spikes. Seemingly random messages would pop up and leave if I waited too long. Eventually, I realized that some of the options were, well, not upbeat, but truthfully. Phrases along the lines of “Bad things happen to everyone,” “Just because this happened, it doesn’t mean there’s something wrong with you,” etc. My job, it turned out, was to encourage the poor bunny to hang on for as long as possible as it slowly slid down the spike.

Realistic images obviously would have made the game component of this episode more tragic and less upbeat, as would normal, non-squeaky voices. The “humor” helps to cut the tension for a discussion of general life happenings we all struggle with but, honestly, may not always get the best advice about. As someone who’s had a few recent hard knocks and few people to turn to, I could see how Everything is Going to be OK could really help someone out. Assuming you can see through its outside, there’s some good commentary on dealing with issues like anxiety and depression, not just as someone who suffers from afflictions, but also how some advice given may not be that helpful or how brutal honesty is really something we all need now and then.

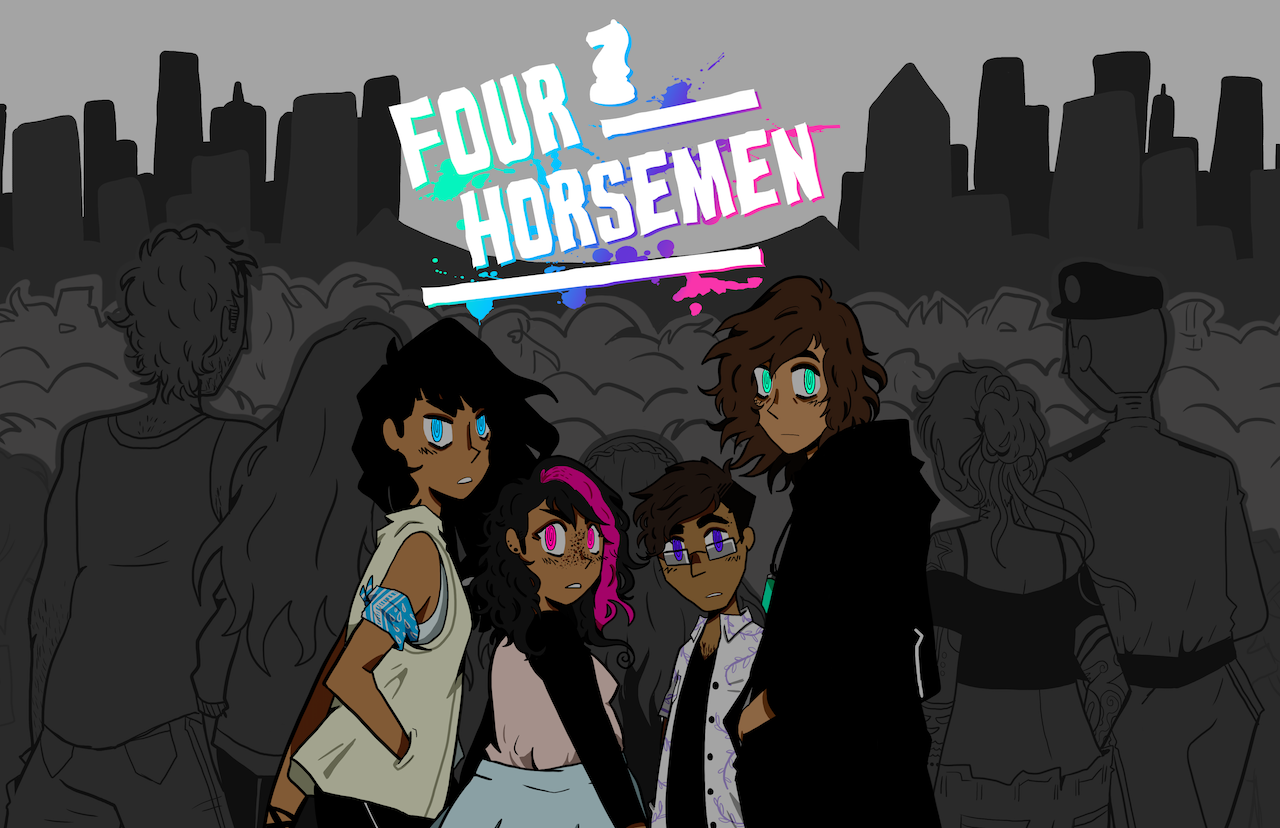

Four Horsemen

It’s odd to me how good the concept of Four Horsemen is compared to what’s out. You play a set of characters on an island who are all minorities but nothing directly related to real world races/ethnicities, though there are some “flavors” that feel familiar. It’s less heavy-handed in a “You’re wrong for thinking this way” manner and more “Can you see how the different perspectives would create tension?” kind of way.

I must admit that from the title, I was hoping for some more immediate connections to the title but, well, the characters and their names didn’t strike me as particularly fitted to Famine, Death, or Pestilence/Conquest, though the character with the blue eyes above does seem to fit a War theme in some ways. The rough anime style could be a turn off for some players, myself included, but I’ve been known to deal with differences in style when the content appeals to me. Perhaps it’s a bit too rough for me, and I don’t just mean the art.

Like Bury Me, Four Horsemen uses language to help immerse the audience. More so than Bury Me though, Four Horsemen uses its own language, which sometimes only very vaguely seems based on a language I’m familiar with. It then fires off several nouns (and maybe other parts of grammar) in the same sentence with little to no points of reference to help the reader understand what those words mean.

Worse, because these are teenagers, their recognizable English isn’t perfect: they have spelling and grammatical issues, which sometimes is supposed to lead to humorous observations or connections, but when combined with the fake language, caused me to struggle with the text. As the game is largely a choose-your-own-adventure with multiple endings, it’s difficult for me to invest in a game that’s asking me to wade through both a fake language (hopefully just one!) and spelling errors, intentional or not. Perhaps that’s why the Steam page is having trouble getting reviews despite one of the developers telling me it’s sold numerous copies since it’s April 2017 release.

I didn’t play through the whole game, but the developers also didn’t bring a demo, choosing instead to bring the full game, so it was difficult for me to walk away feeling like I got an experience. Perhaps if you’re interested in minority experiences, can appreciate the art style, language-immersion options, and the genre, Four Horsemen will be entertaining. If anyone’s actually finished the game, I’d love to hear people’s opinions about it in the comments section!

Ishmael

Ishmael is more of an interactive story than game game. Sure, you can play tic-tac-toe or draw a picture, but most of Ishmael is clicking text. It feels liinear, and even the creator mentions that, at the end of this story about a refugeee boy waiting to see his first puppet show inside the refugee camp he’s forced to live in, you’re essentially forced to take one ending. Creator Jordan Magnuson admitted he originally thought of it as being a short story, but games are his medium so he wanted to do a game. He wanted the game to enforce this idea of the inevitable, and I can understand that to a degree. A person raised in a culture that only praises, say, bread, and has never known cheese, would naturally have a hard time saying “I love cheese more than bread.” However, that doesn’t mean certain parts of one’s

However, that doesn’t mean certain parts of one’s life are completely without choice. Exploring outside your culture, talking to people outside the mainstream, or listening to the other side not only helps to broaden one’s perspective, but makes other paths possible. If Ishmael had focused more on the absent ingredients in his life, like non-violent protesters or parents who focus on their family instead of politics, it might make the player’s journey more meaningful. As gamers, we’re used to options. Taking those options feels like a gameplay error. Highlighting the fact that the player is missing something, or even punishing the player for going down what may be a normal path to us but deviant in Ishmael’s society, might have better highlighted why people in Ishmael’s situation go down the path they do. It’s certainly an experience (and free), and clearly got me thinking about the topic, so it seems Magnuson at least set out what he had planned to do with the game.

Kim

I hesitate to put Kim in this section since there were other period pieces, but few stood out as much as this one. Based on the novel by Rudyard Kipling, Kim is about an Irish boy named Kim growing up in India towards the end of the 1800s. Kind of. He blends in as a local and seems sort of aware of his Irish heritage, but without parents to model his culture for him as a child, Kim is much more Indian than Irish despite his blood. It’s odd to see white people mostly treat him poorly before realizing his heritage. Certain things, like an old priest opening the boy’s shirt to check the color of his skin, are perhaps more shocking in this day and age, making the source material more problematic for modern audiences.

The game is almost like Oregon Trail meets, well, Kim. Your mission, at least at the start, is to help a traveler who, like you, must also beg for their food. You use wit and charm in conversations, strategize how to use your supplies and stats, and explore maps. There’s combat too, but I admittedly didn’t try it, as you can see potential enemies’ field of vision and I constantly felt like there was no way for me to become violent. Normally that’d be OK, but when I saw animals I wanted to try to kill for food, they weren’t even viable targets. It may say something about Hindu culture (admittedly, one was a cow),

The game’s mostly top-down and text based, but the text is a problem. It uses language very similar to Kipling’s, so most modern audiences will struggle with the English. Then there’s the Hindi that permeates the book. To make matters worse, the plot isn’t entirely there. Had I not known the basics of the story (I’d read a plot summary pre-IndieCade knowing that this would be a game I’d check out), I don’t think I’d understand what was going on in the game at all. Fans of the book or those looking to immerse themselves in historical/literary Indian-English empire relations certainly would enjoy the game, but for casual gamers with a casual interest in the game’s topics, Kim will be a big investment.

Oblige

I won’t lie, I had sort of a love/hate relationship with Oblige. The game is basically a side scroller with typing challenges. You play a housewife trying to adjust to her new life in Hong Kong, and no, you don’t speak the language natively. You can communicate well enough to do minor tasks, but the kids are far more proficient than you. Your husband goes out to work so you’re left doing errands for your family. The game is in English, but imagine it as foreign language, as you’ll notice certain people have “accents,” including yourself.

You see, instead of asking you to learn Chinese to understand what it’s like to adapt to a new culture, you’re asked to relearn your keyboard layout for each task. Each key row is randomly generated within itself. That is, “G” onscreen may move to the “A” position, but never the top or bottom row. It may seem small and annoying, but it immediately reminded me of moving to Japan and suddenly having to learn where certain keys were on a Japanese keyboard.

This led to a sort of love/hate relationship with my time in the game. Culture shock isn’t fun. Especially as a PC gamer, the one thing I pride myself on is my typing. Relearning the keyboard for each mini-game, where you rapidly strike the correct button(s) or type out your thoughts, is frustrating. However, it’s also a really good way to think of cultural assimilation: the way you may do things are right for what you normally do, but in a new context, they may not be, and you have to learn how to adjust. Despite the frustration, I was determined to finish my tasks and become more fluid with my keyboarding (boy I wish I could do that with other parts of my personality!).

What’s particularly interesting to me is that another game, Keyboard Sports, also had players using the keyboard in somewhat strange ways. Imagine controlling a character, not with WASD, but with the entire keyboard laid out as a tile map, and moving the character or shooting crossbow quarrels towards the key you hit. Oblige had a meaningful story attached to this kind of gameplay that made it hard to walk away from, while Keyboard Sports felt more “fun” with all its quirkiness and pun-filled humor (fetching “T” for the zen master, finding your proper “SPACE” etc). Both were enjoyable, no doubt, but the way they tackled the keyboard and built a story around it was quite different.

Laguna Levine

Latest posts by Laguna Levine (see all)

- Diversity Experiences of IndieCade 2017 - October 16, 2017