Heaven Will Be Mine is a 2018 visual novel by Mia Schwartz and Aevee Bee. It is the spiritual sequel to 2016’s We Know the Devil, taking with it many of the first game’s naming conventions and decidedly queer romances while shifting the story to space in an alternate universe’s 1981. It’s a gorgeous masterpiece, and you should play it.

Okay, review over, thanks for reading! Visit our Patreon for cool prizes! Like comment subscri-

“There is no future for humanity in space.”

(Spoilers for Heaven Will Be Mine ahead! Consider yourself warned.)

Let’s talk about existential threats.

When you’re nine years old, the world is still a magical place. Reality and fantasy haven’t solidified into their separate spheres yet. Everything you see, touch, taste, hear and smell mixes with the heaven of your imagination. You create entire worlds in your mind and destroy them with reckless abandon. You think it’s absolutely possible for Pokémon to be real.

When you’re nine, the first time you see a dead body solidifies with the kind of oatmeal you had that morning, its consistency and the temperature of the water. You remember the September morning fog. You remember hearing your mother log into America Online and exclaim to the entire house that a plane has hit the Twin Towers.

You’re getting ready for school and your father turns the television on. Your TV screen fills with the image of a smoking building. Another image appears, and it’s the same building but closer, and you see something impossibly small fall out of an impossibly tiny window. The camera tracks with the debris and you realize that you’re watching a body in freefall.

You’re lucky the resolution isn’t better, and the zoom lens on the television camera doesn’t zoom in further. Heaven has fallen.

Nine years old is too young to understand global politics. But it is the perfect age to understand pain. You spend countless hours over countless days crying in private, the falling human body replaying in your mind’s eye over and over. You stifle your tears around other children. Displays of patriotism pop up everywhere around you. You let yourself get swept away in them.

“We’re thankful for our cradle’s graces, but we’re not coming back”

Existential threats have a funny way of changing when you aren’t looking. Seventeen years ago, barely anyone fluttered an eyelash when the United States declared war on terrorism. We built a coalition. We had an axis of evil. When you’re nine, and you’re filled with other people’s pain, this narrative feels right. It’s simple.

You get older. The narrative gets muddier and muddier. Suddenly, you’re 26 years old, and the pain you felt as a child hasn’t gone away, but you’re no longer on the same side.

Who is our existential threat today? Is it al-Qaeda? Is it ISIS? What about Russia? Is North Korea a contender? Have we considered Venezuela, or Iran?

Maybe antifa is our new existential threat.

Maybe it’s the media.

Who knows? Maybe it’s ourselves.

“Earth or heaven, we are just short of 100% human. So let’s see how much less than 100% we can get.”

Existential threats aren’t unique to entire countries. Everyone can have one. In fact, most people do. According to a paper by Gilad Hirschberger from the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya School of Psychology, existential threats are what cause most intergroup conflict.

Hirschberger’s study finds four different kinds of existential threats ranging in scale from the individual to the national: “(a) An individual future-oriented physical threat – personal death; (b) A collective future-oriented physical threat – physical collective annihilation; (c) a collective future-oriented symbolic threat – symbolic collective annihilation; and a collective past-oriented threat – past victimization.”

Using these threat types, Hirschberger was able to synthesize a new psychological model: the “Multidimensional Existential Threat” Model, or MET. In creating the MET model, Hirschberger believes that psychologists and researchers in related fields can gain a much more nuanced understanding of intergroup conflicts.

Heaven Will Be Mine follows three pilots, Saturn, Luna-Terra and Pluto, as they spend their last week in space after the rest of humanity figures out that there was no meaningful Existential Threat waiting for them beyond the solar system, and opts to turn its back on space exploration altogether.

“Hey, it’s not like we’re idiots. We know we’re doomed.”

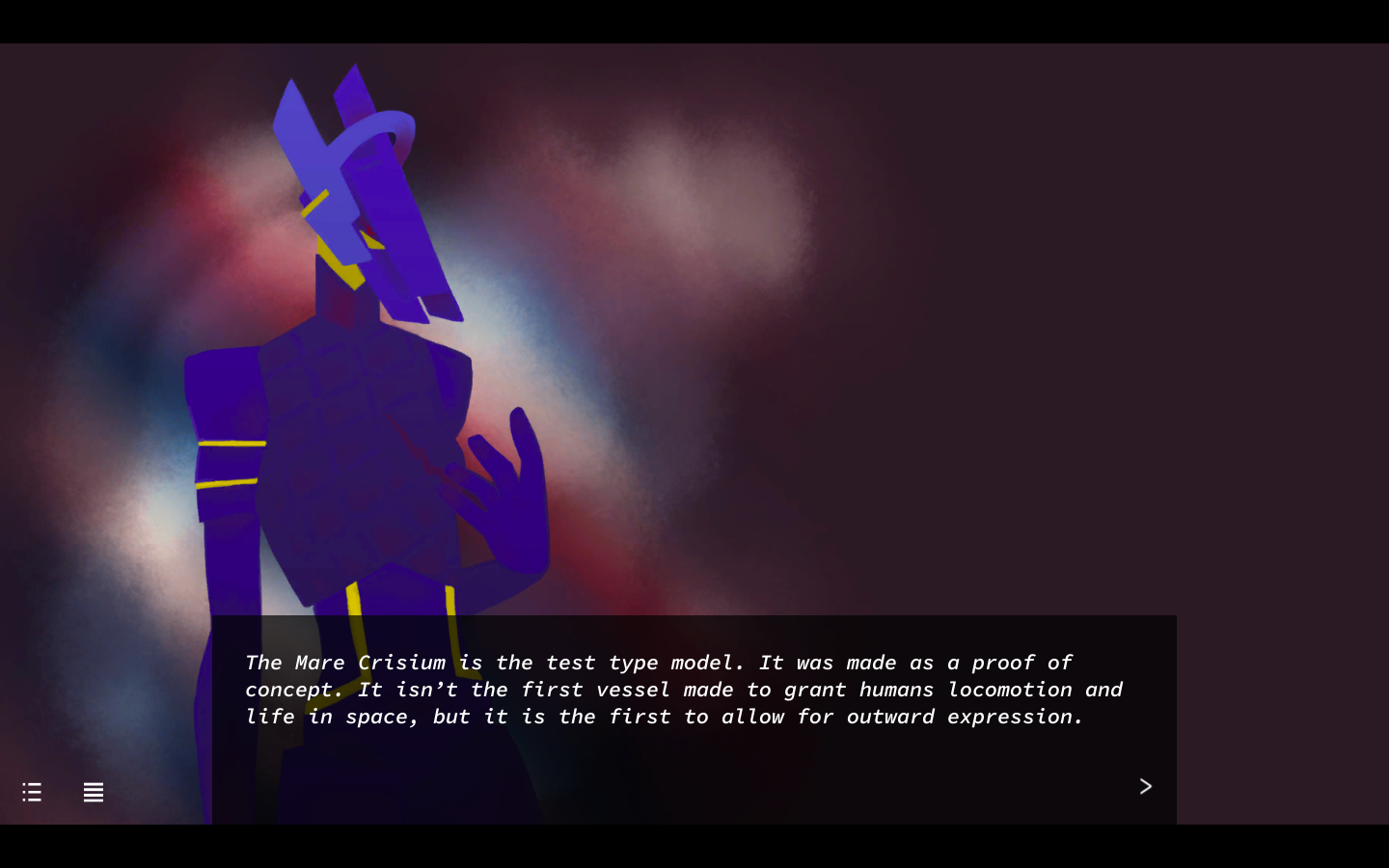

These pilots represent each of the story’s main factions, and drive a ship that falls somewhere between a Gundam and Evangelion Unit-01. Saturn pilots the stolen prototype Ship-Self String of Pearls, and is a member of Celestial Mechanics. Luna-Terra flies the first-generation Ship-Self Mare Crisium for Memorial Foundation. Pluto is in charge of the bleeding-edge Ship-Self Krun Macula for the rebel group Cradle’s Graces.

Each faction, and each pilot, has their own goals and priorities they’ll follow throughout the game. Memorial Foundation’s goal, for example, is to bring humanity back into Earth’s embrace forever. Celestial Mechanics wants to lean into earthbound humanity’s desire for an alien threat. Cradle’s Graces wants humanity to live in space.

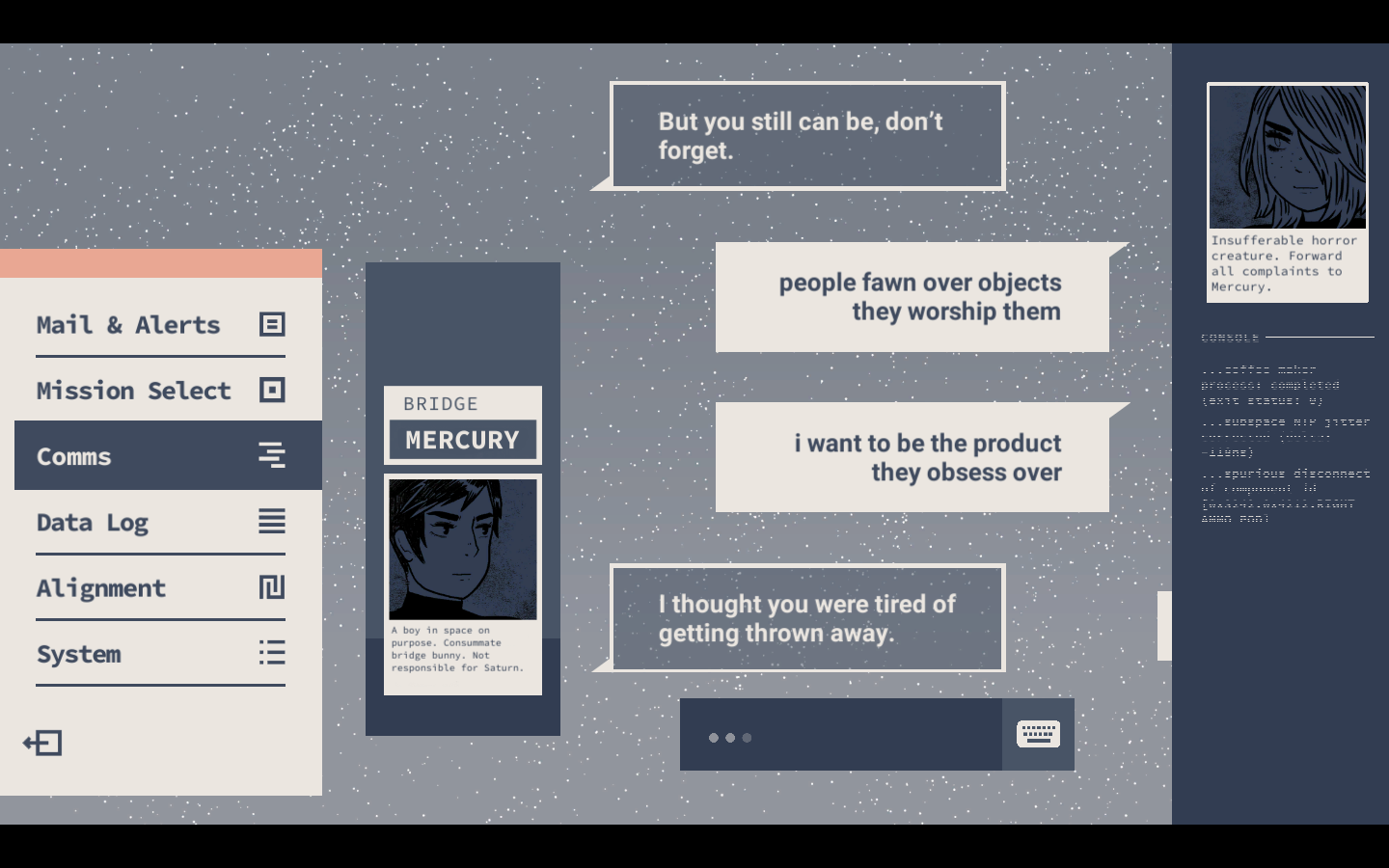

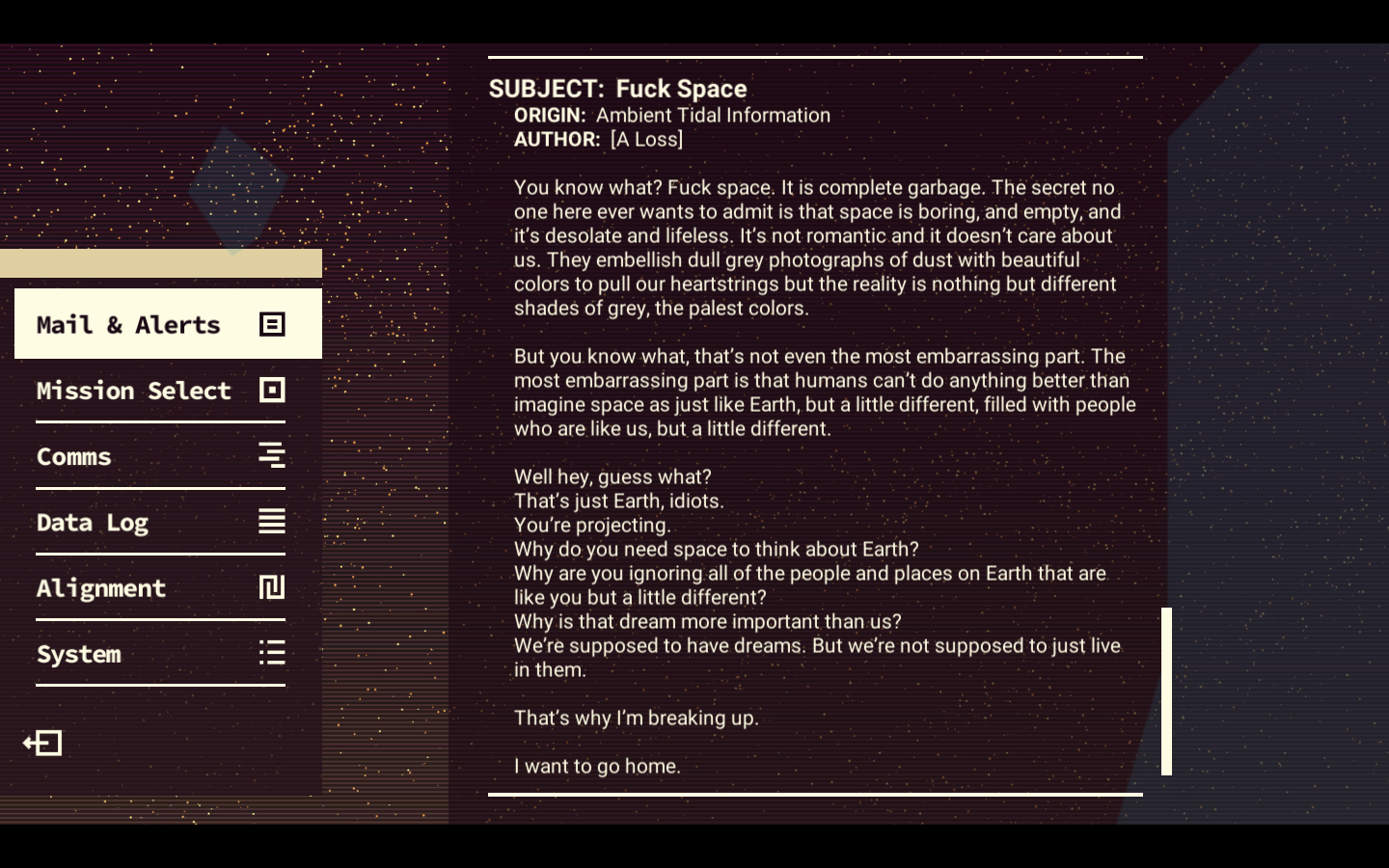

The game’s design makes it easy to manage these competing goals. Players interact with three main areas: an email inbox, a chatroom and the mission page. Lore is piped in through the inbox, giving players additional context with the broader story. Each playable character gets a companion NPC who adds depth in the chat. And the mission page is where major events occur. There are eight missions spread out over nine days, and each of them has the opportunity to advance either the player-character’s faction or one of the other factions. After each mission, players are taken to an alignment chart, where they can see how much influence, or “gravity,” each faction is exuding on the game.

“Until no one is forgotten, and all are remembered.”

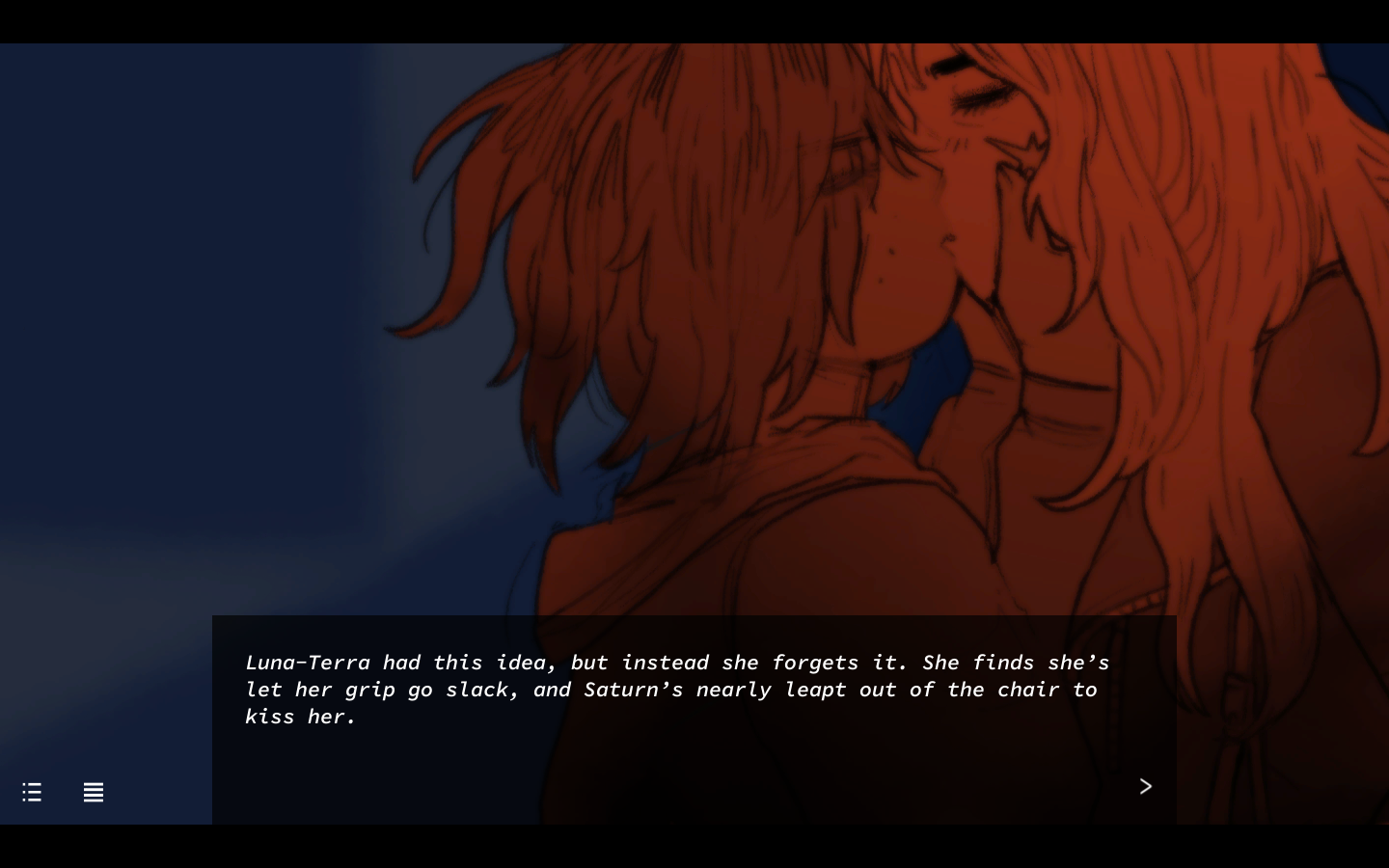

In my first playthrough as Saturn, I made choices that made sense to me. These choices didn’t adhere to a specific faction’s influence. Instead, I chose to advance Saturn’s relationships with both Pluto and Luna-Terra. The game ended with the Memorial Foundation more or less getting what it wanted, but Saturn, Luna-Terra and Pluto were together as a polyamorous triad.

Playing the game in a straightforward way doesn’t always yield a good ending in Heaven Will Be Mine. Experimenting with choices and relationships makes for much more interesting gameplay. It’s not that none of the characters care about their motivation – it’s that sometimes, smooching is more important than ending an interplanetary war. Especially when nobody else cares about that war.

And as it turns out, there is an enemy underneath the ennui.

Celestial Mechanics’ leader, Iapetus, turns out to be a real asshole in the game’s universe. He is more aligned with the people on Earth who want to leave space or find another Existential Threat than anyone else. He also experimented on children in unsavory ways, according to Heaven‘s lore. Iapetus wants to turn the Ship-Self pilots into humanity’s next Existential Threat. This will keep the space program open. He will get to keep his job.

“We measure Earth by Culture.”

When you strip away politics, ideology and identity, the biggest existential threat any of us face is that of life. Life eventually ends. All our individual hopes and dreams and aspirations end with our deaths. And yet, we continue to have hopes, and dreams, and aspirations. We pass them on, if we can.

Albert Camus, an absurdist philosopher, wrote, “Seeking what is true is not seeking what is desirable. If in order to elude the anxious question: ‘What would life be?’ one must, like the donkey, feed on the roses of illusion, then the absurd mind, rather than resigning itself to falsehood, prefers to adopt fearlessly Kierkegaard’s reply: ‘despair.’ Everything considered, a determined soul will always manage.”

Right now, everyone is concerned about a looming, existential threat. It is almost always referred to in terms of “the Other.” The alt-right just took to the streets in Portland, Ore. to show the world how strong they are in the face of their existential threat. They believe that white people are going extinct. They believe that “western civilization” is under attack by the rest of the world. Theirs is the dying gasp of an outdated worldview, and we are happy to be their existential threat.

In a meaningless universe, we create our own meaning. If that means we become existential threats to a humanity that prefers the safety of its own gravity to the wonderful weightlessness of space, that’s okay. Space is bigger than we are. We have more room to grow.