With the recent release of Emily Is Away Too, I decided to revisit its prequel game, 2015’s Emily Is Away. For the uninitiated, in both games, the entire story unfolds within the confines of an AIM-esque chat program, in which you converse with your friend, the eponymous Emily. The chatlogs chronicle the ups and downs of your relationship, over the span of five years.

The protagonist is a blank slate and essentially a stand-in for the player. In my first playthrough, I decided to make the protagonist a Chinese American boy named Wupeng (because the name Wupeng is inherently awesome). Though the story is beautifully told, it is at its core a fairly conventional lost love narrative: a boy with a not-so-secret crush on his female best friend does not act upon his feelings until it is too late. Due to physical distance and unresolved sexual tension, the two gradually drift apart.

Which all feels like well-trodden territory (and it is), but the magic lies in the telling; we’ve seen this story before, but never in this ultra-nostalgic, bite-sized format. However, the novelty of its AIM chat trappings were not enough to blind me to some of the overly conventional elements of this male-centric tale: due to the nature of the story, it’s all too easy for the audience to develop feelings of entitlement towards Emily, to think of The Other Man as a shadowy threat, and to adopt a self-victimizing “nice guy” mindset.

Thus upon revisiting the game, a certain idea percolated in my mind: what if I played Emily Is Away with a female protagonist instead, one who is presumed to have an attraction to girls?

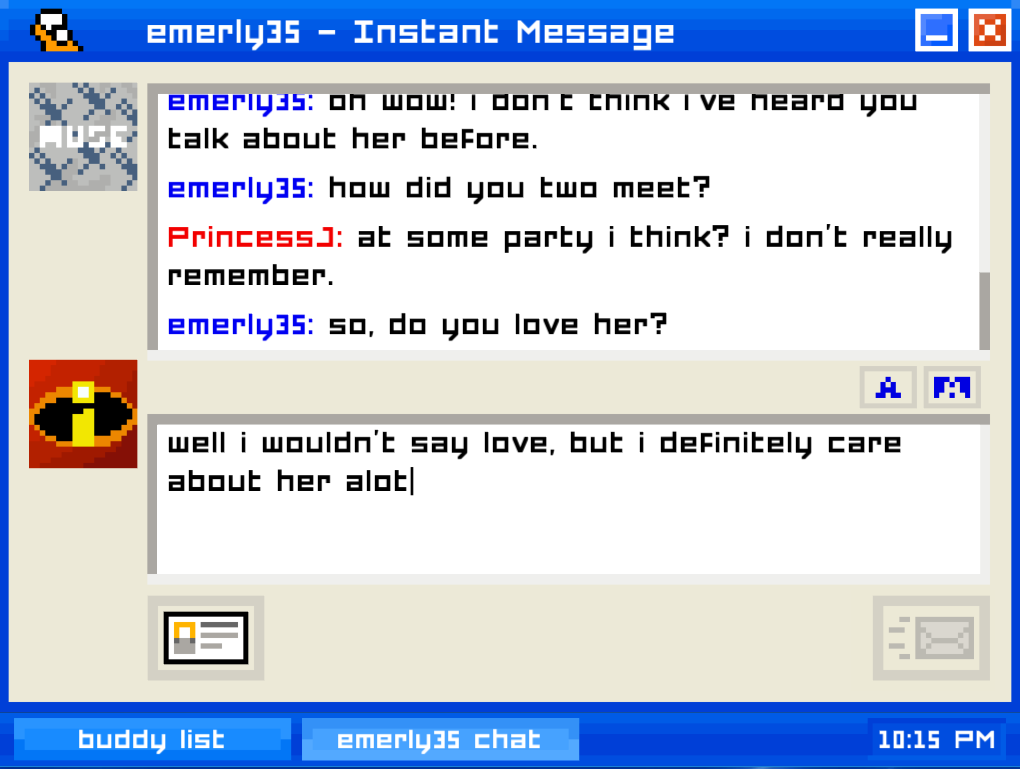

Jasmine and Emily discussing Jasmine’s latest crush, Emma.

A new perspective.

I named this new character Jasmine. Note that this actually falls within the boundaries of authorial intent; at the onset of the game, the random name generator offers traditionally Western, masculine-sounding names such as Brad or Chris, but also feminine-sounding names such as Rachel or Kimberly. Moreover, the narrator’s gender is never made explicit, which allows the wiggle room to play as virtually anyone. And when playing as a female, the entire story changes—for the better.

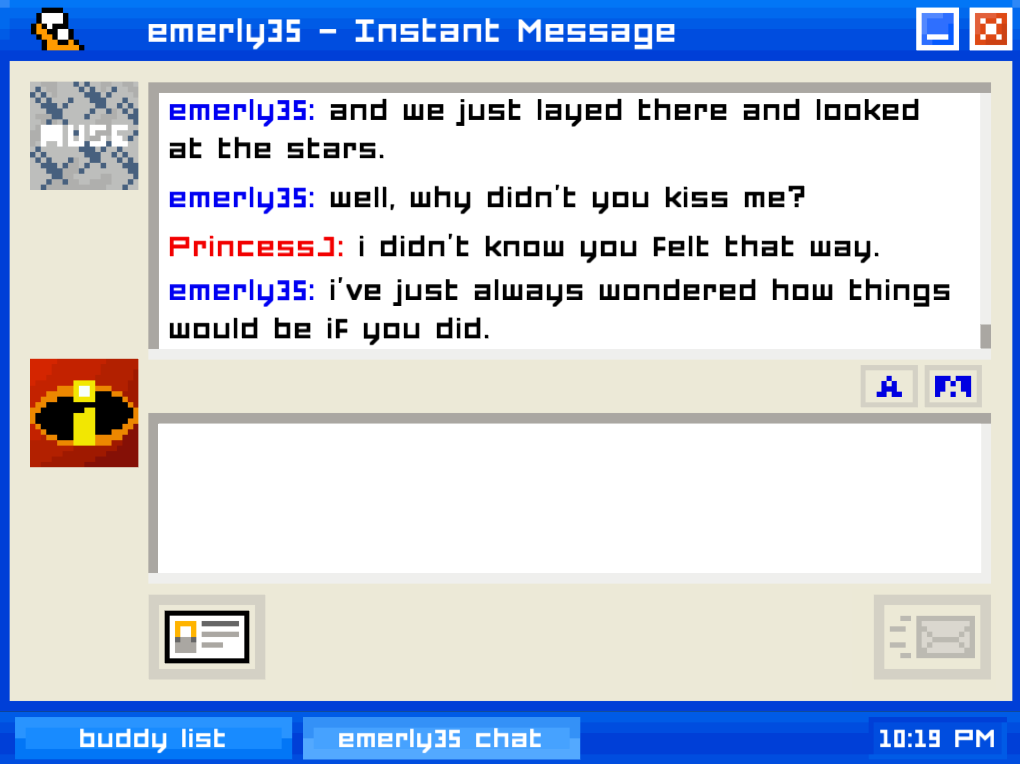

When told through the eyes of a female character, Emily Is Away is still at its heart a story of lost love, but the shell surrounding that heart morphs almost in its entirety. The interactions with Emily—which are vague enough that you never truly know what she’s thinking—adopt new layers of meaning: the constant doubt, the indecision, the inaction, and the confused, messy, and even passive aggressive exchanges all seem more profound.

“I didn’t know you felt that way.”

In this new version of the game, the “nice guy”-ness of the protagonist melts away. When playing as Wupeng, his frequent invocations of friendship (“I just want you to know that I really care about you, Emily.”) always felt a bit icky, his ulterior motives made all too plain. For better or worse, we’re primed to look at most male-female friendships through the filter of romance; of course Wupeng—and the player—has at least the slightest suspicion that his attractive, boyfriend-less female best friend might reciprocate his feelings for her. Any claims to total ignorance come off as obtuse and disingenuous.

In comparison, Jasmine’s longing for Emily feels less greedy, less insidious. Gone is the entitlement that otherwise pervades the narrative. Unlike Wupeng, Jasmine is far more likely to genuinely believe that Emily is off limits to her. After all, Emily has a boyfriend, and she is clearly attracted to men. It would be delusional to entertain the idea that she has a chance. Right?

In this way, the protagonist’s entire narrative and backstory remolds itself into something quite different. Wupeng is scared that Emily will reject his feelings and that his confession might damage their friendship. For Jasmine, the stakes are higher, the rejection wholesale. And when the risk is so high, why gamble at all?

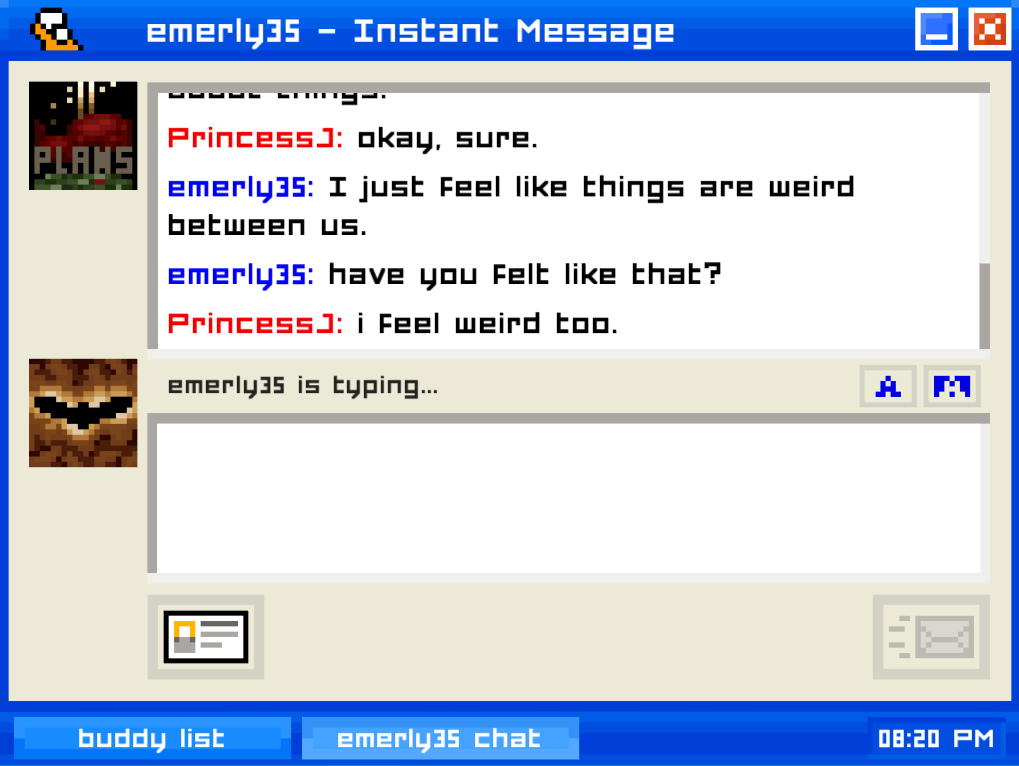

Jasmine and Emily, post-hookup.

Then there’s Emily herself.

Critics of the game often find Emily too confusing and mercurial, a mess of adolescent emotion delivered via chatbox. Jasmine’s perspective allows for a more forgiving interpretation of her character. After all, Emily is not only contending with an altered perception of her friendship with Jasmine, but also an altered perception of herself and her own sexuality.

When Emily later insinuates that Jasmine took advantage of her after a night of heavy drinking, the accusation feels charged with a greater potency; it recalls to mind real-life stories—including stories I myself have personally heard— of those who lash out in anger and confusion after their first homosexual experience, and who go so far as to claim that their partner is to blame for leading them astray. In Jasmine’s story, the pain lurking behind Emily’s words is rawer, the chaos of her mind more keenly felt. It feels like a truer representation of the primary struggle of one’s adolescent years: gaining a better understanding of others, but also of oneself.

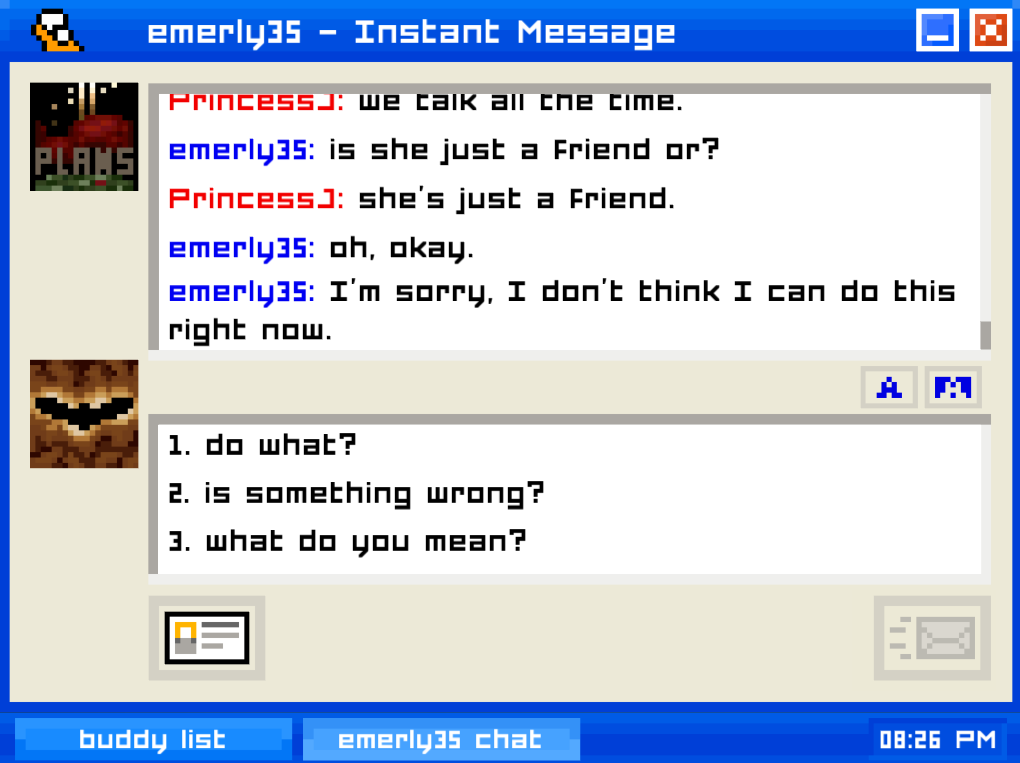

Emily inquires about Emma.

Emily Is Away does not have a happy ending. Those who have played the game seem to differ in their final impressions of Emily. Some dismiss her as crazy. Some think time, distance, and lack of communication eroded their relationship beyond repair. Some claim that fate and the inevitability of their separation is the axis on which the story pivots.

With Jasmine, I can unearth a more personal and intimate explanation. Emily’s rejection of Jasmine is also a rejection of a version of herself, of a lifestyle that seemed so possible until it wasn’t. It is easier to conjure a rationale behind Emily’s increasingly distant behavior and to fill the considerable gaps that pepper the narrative. It is easier to imagine why Emily would reject Jasmine so completely.

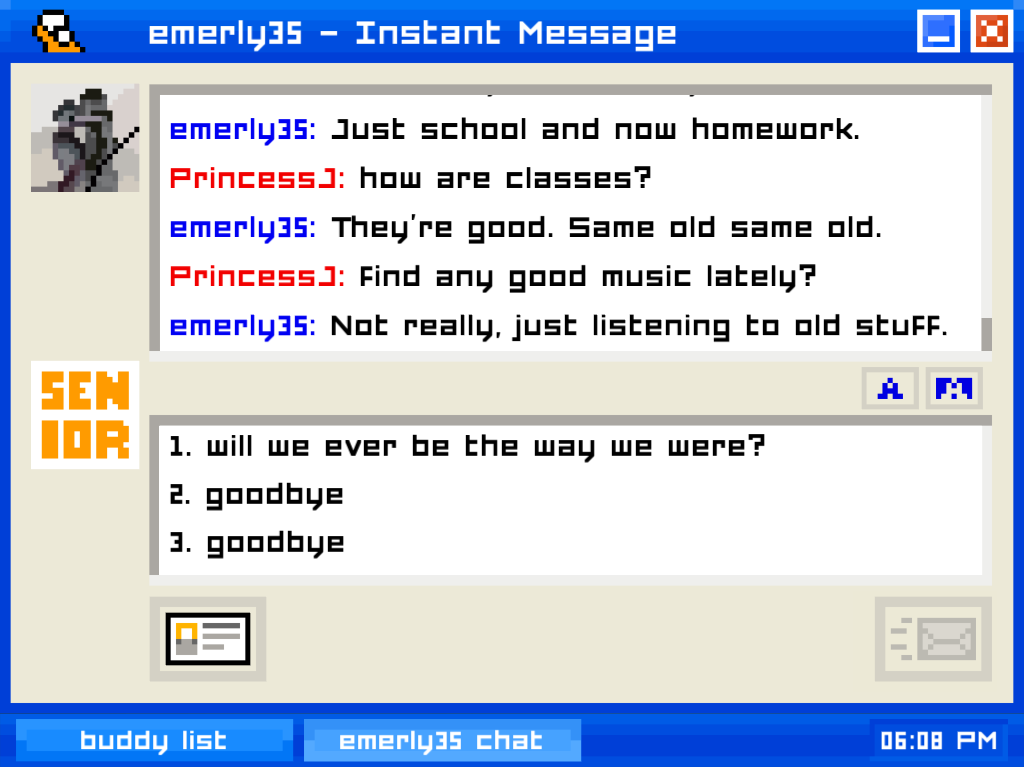

“Goodbye.”

One of the reasons I found this experiment of mine so interesting is that, though the game itself remained unchanged, simply switching to a female protagonist wholly improved my experience of playing it. This other, female-driven version of Emily Is Away offers a richer, more layered, and more emotionally complex story, one that you can read far more into. It’s only the limitations of our imaginations—and ingrained notions of what romance stories are “supposed” to be—that might inhibit us from forging these alternate paths.

I have yet to play Emily Is Away Too, but when I do, I will continue to play as Jasmine. And as with its predecessor, I hope this new game will allow me the freedom to do so.

Helen Liutongco

Latest posts by Helen Liutongco (see all)

- Of White Samurai and Internalized Racism - August 21, 2017

- Fire Emblem: Heroes Needs All The Shirtless Men It Can Get - July 5, 2017

- ‘Emily Is Away’ Is Good But A Female Protagonist Makes It Better - June 19, 2017