I knew I’d found something special in Cd Projekt Red’s The Witcher 2 when I saw this achievement:

Friend To Trolls – Spare all Trolls in the Game – 15 G.

I’d just started gaming again after a two year hiatus. I was rusty, and The Witcher 2 can be tough. I was reacting, not exploring; throwing signs at any potential threat, not knowing I had a choice. When I saw the achievement, I’d already cut down two of the oddly adorable idiots. I felt like a monster. Next playthrough, not a drop of troll blood stained my silver, and I fell in love with The Witcher‘s universe. It embraced a truth we rarely see in fantasy; that the clear cut, black and white, orcs and men dichotomy is too simple, too convenient. That the notion of Good Guys is a storybook conceit.

Story time, then…

Once upon a baffling example of legal fuckery, a law known as Corporate Personhood granted US corporations the same basic human rights as people. The 14th amendment – originally drafted to grant emancipated victims of slavery full citizenship – also applies to the entity known as Walmart.

Many years later, in the faraway land of early 20th century New York, Edward Bernays – who would later be known as ‘The Father of Public Relations’ – set down the groundwork for the modern advertising industry with a series of books, including the ominously titled Crystallising Public Opinion.

Many years later, in the faraway land of early 20th century New York, Edward Bernays – who would later be known as ‘The Father of Public Relations’ – set down the groundwork for the modern advertising industry with a series of books, including the ominously titled Crystallising Public Opinion.

‘The problem for the public relations counsel is to create in the public mind the close relationship between the hotel and … the things the hotel desires to stand for’ – Bernays

He had some help writing those books. Namely, from his uncle; Sigmund Freud, who implemented psychoanalysis to shape PR as we know it today. The result? Both in the eyes of the law, and the wider culture, corporations had taken on personalities of their own. No longer were they apolitical, faceless titans but superheroes of convenience, abundance and value. It’s why, when you think of KFC, you picture the kindly, whiskered face of Colonel Sanders, and not bloodied factory farm conveyer belts and underpaid staff. Or with Nike, chiselled athletes instead of emaciated sweatshop workers. It’s why, when you think of CD Projekt Red, you don’t think of poorly paid Polish developers suffering through lengthy crunch periods, you picture Good Old Games, Free DLC, and passionate, affable Marcin Iwiński.

Create the problem, sell the solution

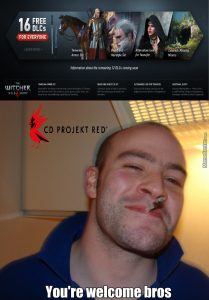

In 2014, five months before the release of The Witcher 3, CD Projekt Red released a statement on GOG.com, detailing ’16 extra content packs coming free for everyone’.

‘As gamers’ The message from joint CEO Iwiński began ‘we nowadays have to hold on tight to our wallets, as surprisingly right after release, lots of tiny pieces of tempting content materialize with a steep price tag attached. Haven’t we just paid a lot of cash for a brand new game?’

The cultural gaming landscape in late 2014 was fervently anti-industry. The previous year, EA had been voted Consumerist‘s ‘Worst company in America’ for the second time running, on the back of Sim City‘s disastrous launch, Dungeon Keeper‘s freemium reboot and Dead Space 3‘s drastically altered tone. The hugely hyped Watch Dogs and Destiny had resolutely failed to meet expectations. WB Games undisclosed paid promotions for Shadow of War had come to light. In the midst of it all, consumer advocates like Jim Sterling, John Bain and Joe Vargas were taking triple A to task over every shady practise to Youtube audiences numbering in the millions, revealing industry tactics and mythologising their trickery in parodic characters like Vargas’s Corporate Commander. It was through this miasma of spilled Mountain Dew and Dorito flavoured rage spittle that CD Projekt rode in on their armoured white stallion, ready to save the day. Only this horse armour wouldn’t cost gamers a thing. CDPR, as they said in their statement, had ‘decided to do it differently’. The culture ate it up. CD Projekt were heroes.

The cultural gaming landscape in late 2014 was fervently anti-industry. The previous year, EA had been voted Consumerist‘s ‘Worst company in America’ for the second time running, on the back of Sim City‘s disastrous launch, Dungeon Keeper‘s freemium reboot and Dead Space 3‘s drastically altered tone. The hugely hyped Watch Dogs and Destiny had resolutely failed to meet expectations. WB Games undisclosed paid promotions for Shadow of War had come to light. In the midst of it all, consumer advocates like Jim Sterling, John Bain and Joe Vargas were taking triple A to task over every shady practise to Youtube audiences numbering in the millions, revealing industry tactics and mythologising their trickery in parodic characters like Vargas’s Corporate Commander. It was through this miasma of spilled Mountain Dew and Dorito flavoured rage spittle that CD Projekt rode in on their armoured white stallion, ready to save the day. Only this horse armour wouldn’t cost gamers a thing. CDPR, as they said in their statement, had ‘decided to do it differently’. The culture ate it up. CD Projekt were heroes.

This is how a huge company cements their reputation as plucky underdogs. How the work of hundreds of people is amalgamated and attributed to half a dozen charismatic individuals. Why everyone knows Ken Levine but no-one can name the person who stayed at the office late coding Bioshock‘s bullet physics. How Valve was raised to deific status via a few great games over a decade old and few hundred Gaben memes. It’s why, when CD Projekt revealed the downgraded Witcher 3, barely anyone kicked up a fuss, despite the fact that Ubisoft had been publicly pilloried a few months earlier over a similar downgrade in Watch Dogs. Could it also be why, despite rumours circulating on Neogaf about heavy crunch time at CD Projekt as early as October 2014, it took this long for anyone to really take notice? To their credit, CDPR did respond to said rumours…with a statement from communications executive Michal Platkow-Gilewski that they didn’t ‘comment on rumours’:

‘PR aside, if you have any doubts about Wild Hunt’s quality, have a look at the 35-minute gameplay video we published some time ago’.

PR aside, indeed. The question remained though; if CDPR didn’t comment on rumours, why did they feel the need to publicly respond to a short post from an anonymous NeoGaf user via industry giant Gamespot?

Revolving doors.

At the time of writing, of the 50 reviews on Glassdoor from current or former CD Projekt Red Employees, 24 are ‘mixed’ – rating them at three stars or less. Of those, eleven are 2 stars, and seven are 1 star. Fourteen of them are from this year. Reading through them paints a negative picture, but not an entirely new one. Claims of ‘year long crunch periods’, twelve hour minimum days, and tumultuous company politics are common in reviews from the past two years. More recent ratings, such as the poetically titled ‘Mad King, absent minded aristocracy, and survivalists’ describes the ‘CEO’ as ‘erratic and chaotic’ with ‘no interest in gaming’. ‘Crunch here is insane’ it continues. The reviewers ‘advice to management’?:

‘Please leave making games to people who actually who play them, make them and love them’

Glassdoor, of course, is anonymous. I could have posted a review myself if I wanted to. Some of the statements about CDPR on there are admittedly bizarre, including the assertion that ‘The company has an annoying constant phobia of Russia’. As with the NeoGaf post though, it does beg the question to why CDPR chose to respond, a move that could just as easily be seen as lending legitimacy to the concerns. Crunch in games is nothing new, and, if there’s truth to the rumours, it’s certainly not something CD Projekt are alone in. According to the International Game Developers Association’s 2015 Developer Satisfaction Survey, 62% ‘indicated that their job involves crunch time’. As consumer expectations rise and the industry responds, it doesn’t look like this sort of practise is going away anytime soon. The 2015 Guardian article ‘Crunched: has the game industry really stopped exploiting its workforce?’ featured this quote from an EA engineer:

Crunch in games is nothing new, and, if there’s truth to the rumours, it’s certainly not something CD Projekt are alone in. According to the International Game Developers Association’s 2015 Developer Satisfaction Survey, 62% ‘indicated that their job involves crunch time’. As consumer expectations rise and the industry responds, it doesn’t look like this sort of practise is going away anytime soon. The 2015 Guardian article ‘Crunched: has the game industry really stopped exploiting its workforce?’ featured this quote from an EA engineer:

‘It’s the classic two-out-of-three question: you can’t have good, fast and cheap; pick two. There are certain levels of consumer expectations and quality you can’t sacrifice, so manpower gets hit’

Neutral…or indifferent?

So where does this leave us as consumers? The responsibility lies with the companies that enforce these practices, but I feel that we can start by asking more questions, by holding these publishers accountable more often. By adding our voices to the conversation, and by being aware of the struggles that go into development. It’s not easy to look at the meal on your plate and be mindful of every link in the production chain that brought it to you. It’s not easy to watch impressive trailers and interviews with charismatic PR reps and see the months of sweat, tears, caffeine, shitty food, and disrupted family lives that have gone in to the games we love. But it’s something worth keeping in mind.

CD Projekt Red’s incredible games showed us all the importance of questioning the narrative of easy heroism. It’s time we accept the realities of game creation on this scale can’t produce easy heroes either. At least, not the ones we hear about.

Nic Reuben

Latest posts by Nic Reuben (see all)

- These Horizon Zero Dawn Photographers Find the Soul in the Machines - March 16, 2018

- A Completely Objective Review of An Apolitical Game - February 9, 2018

- This Horizon Zero Dawn Photographer Brings the Post Apocalypse to Life - January 17, 2018