There’s no such thing as a good loot box, all of them are capital ‘B’ for Bad no matter which way you slice them. We’ve established that much: so what are we going to do about it?

As NPD analyst Mat Piscatella outlined to GamesIndustry.biz, for all the furore and the calls for boycotts, the microtransaction and loot box controversy is not affecting game sales. Since video game marketing budgets and the strength of the Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings and Assassin’s Creed brand names will win out over capslock forum posts, it’s unlikely that this will ever work.

An actual solution that might work, though? Raising the prices of games.

Development Costs Are On the Rise

Call of Duty: WW2’s ‘Supply Drop’ loot boxes saw backlash from some fans of the shooter series.

Loot boxes and microtransactions are not the money grab that you think them to be. Rather (in many cases at least) they’re a direct result of ballooning game development sizes and rising expectations.

By Kotaku‘s estimates, developing a game costs $10,000 per person per month. It means that a game from a major publisher (your Assassin’s Creeds, your Destinys and your Call of Dutys) could cost upwards of $140 million to make. And this is even before you consider the live services and post-launch content that have become almost mandatory at this point.

Take this quote from Marcuss Nilsson, the executive producer of Need for Speed Payback, in a recent interview with Rolling Stone‘s Glixel:

“It’s clear prices [of video games] haven’t really gone up. That’s clear. I also know that producing games is more expensive than it has ever been. The game universe is changing in front of us now. We see more people playing fewer games for longer. Engagement is important. But how do we deliver longer experiences?

The bottom line is that it’s very hard to find this golden path that’s liked by everyone. We make games that are $60 and some might think that it’s worth $40. What’s the value in the package delivered? Something like GTA 5 and GTA Online versus The Last of Us, which you can play through in 10 hours. How do we value that? Thats probably a long discussion.”

More Money Than Ever from Microtransactions

Ubisoft reveals exactly how much it makes from loot boxes, microtransactions, and DLC.

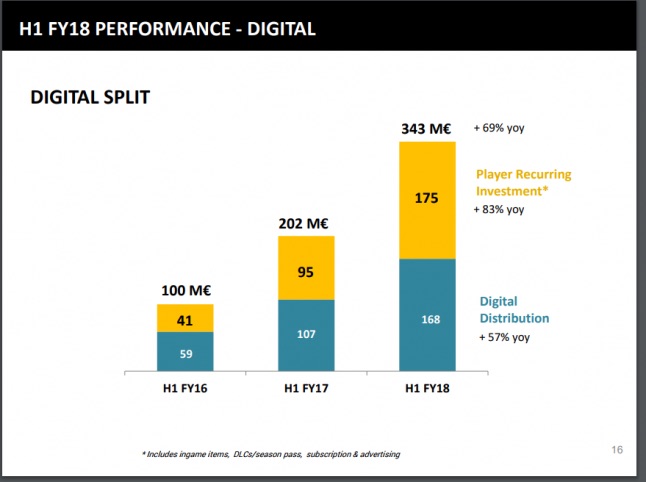

And compare this to data recently revealed by Ubisoft: in the first half of its financial year (FY2018), Ubisoft made more money from DLC, microtransactions, and loot boxes (51%) than it did digital game sales (49%).

According to NPD (via ESA), digital game sales already make up 52% of overall game sales in the United States. Presuming that Ubisoft game sales are split similarly, it means that a significant portion of its game revenues (overall) are thanks to the very same loot boxes that you hate.

Loot boxes and microtransactions seem to be an unfortunate result of a growing games industry but is raising the entry free a more desirable solution? Doing so would mean that developers and publishers would no longer have to rely on recurring payment models and systems as the initial purchase price would help to immediately recoup that cost.

But would you be willing to pay $120 instead of $60 if it meant that you wouldn’t have to face exploitative RNG mechanics? This is the question that players will have to face if they are to demand loot box-free games.

You can answer in the comments.

Jasmine Henry

Latest posts by Jasmine Henry (see all)

- Twitch Spambot Drama Highlights Another Side to Harassment Issue - January 25, 2018

- Overwatch League Skin Unlocks Have a Dumb ‘Easter Egg’ - January 11, 2018

- Call of Duty: WWII’s Female Soldier ‘Rousseau’ Deserves Her Own Spin-Off - December 8, 2017