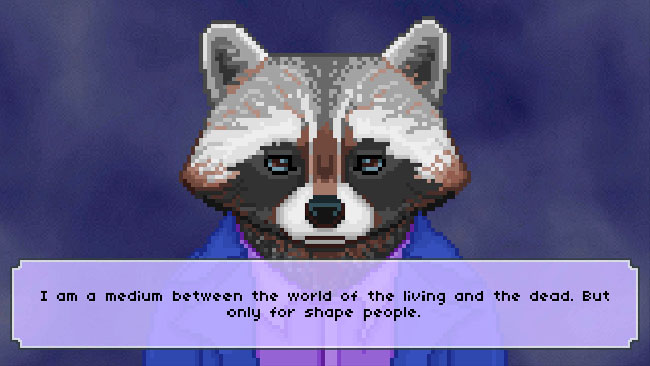

Cliqist recently highlighted The Raccoon Who Lost Their Shape, a quirky occult game about the eponymous Raccoon and their ability to communicate with the ghosts of sentient shapes. Developed by Cat Night Games—a subdivision of FilmCow, Jason Steele’s indie film company that created the viral hits Charlie the Unicorn and Llamas with Hats—and distributed on itch.io, The Raccoon Who Lost Their Shape is a free-to-play browser game.

Beneath its odd setting, point-and-click gameplay mechanics, a branching dialogue system, and the gradual plot reveal of an ongoing search for a loved one, The Raccoon Who Lost Their Shape features a culture of discrimination in its worldbuilding.

(Warning: Spoilers for the game are below.)

The Pentagon

The game’s first case revolves around Raccoon assisting an amusing jerk of a character, a pentagon so convinced that sides and angles are the best, he had to convince his circle friend into accepting that mindset.

At first it feels like a joke, just another facet of a game with the bizarre scenario of a spiritual raccoon medium surrounded by a world of sentient shapes. It’s ridiculous for the pentagon to believe he’s superior because of how many sides he has, and that his circle friend is inferior for lacking such things.

Over the course of The Raccoon Who Lost Their Shape, the arrogance of shapes with more sides gets a little extra dimension to it, with the implication that there is a cultural importance to sides and angles that goes over the head of a non-shape like Raccoon.

And that’s what Raccoon is seen as in this world populated by sentient shapes—if they’re not one of them, they’re just a non-shape. There is no other distinct label for Raccoon except recognizing what they aren’t, and what they’re not a part of.

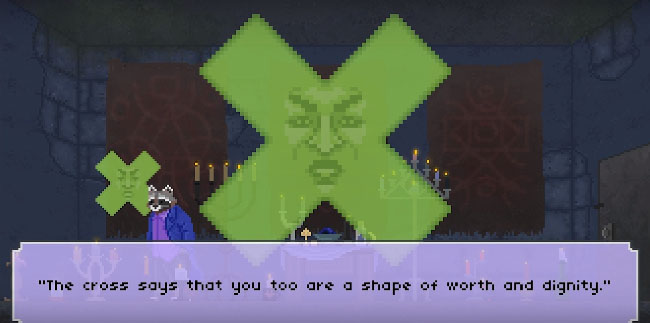

The Cross

Eventually Raccoon summons the ghost of a cross, someone they’ve communicated with multiple times in the past. This cross was famous in life, valued for their many sides and singing ability; and they have had many admirers come to Raccoon in an effort to communicate with them.

But in the game, the cross is the first to challenge what seems to be their world’s cultural belief in the superiority of sides and angles. Though they have the advantage of having 12 sides, the cross seems critical of the societal beliefs that deem them exceptional.

The fans that have repeatedly asked Raccoon to summon them are often dissatisfied with their own appearance, upset that they do not have as many sides as their idol. For each of them, the cross has Raccoon send a message of encouragement, telling them of their importance, no matter their number of sides.

This feels like an echo of real-life situations where people admire celebrities that are held up as the height of beauty, but feel their own self-esteem lower because they don’t look like them.

A cross may have been chosen to be the first shape to challenge this in-game world of discrimination because of their many sides, to present the idea that even those born with all the advantages can realize the true nature of an unjust system.

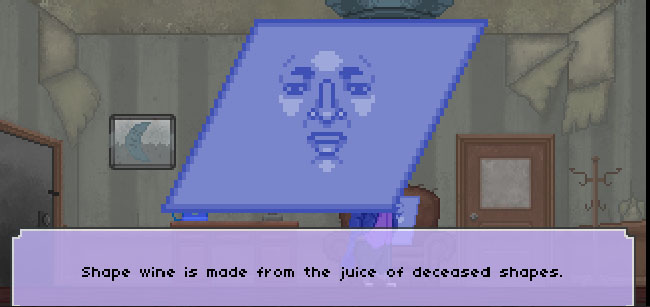

The Diamond

The game takes a startling and even weirder turn when Raccoon helps a client who gives him a wine bottle that was literally made from the corpse of a shape—and is now meant to be a tool for summoning the shape that was literally turned into wine.

But the cultural and widespread belief in the superiority of sides grows even more serious and grave with the new case.

This client explains that she was born with four sides and unable to stand upright, which fit society’s definition of a rhombus; but she now identifies as a diamond. She may not stand upright, but she has as many sides as a diamond, and believes she counts as one.

But her diamond mother—who can stand upright while having the appropriate number of sides—rejected her because she was not upright, because she saw her as a lesser shape, a rhombus.

A rhombus who identifies as a diamond could be seen as a parallel to transgender individuals—and this character’s estrangement from family unfortunately echoes the unfair hardships they can face.

Shades of other types of discrimination can be felt with this case. For example, the diamond mother disgusted with how her child wasn’t born upright could reflect prejudices against those who are not considered able-bodied.

With this case, the game adds other levels of discrimination to the society of shapes, and further reveals its harshness and absurdity. A shape could be born with the right number of sides, but be categorized as a lesser social class if even just their physical alignment does not fit the socially accepted mold.

Though her mother is now dead, Raccoon’s client still wants closure with her. But when Raccoon summons the client’s mother, he learns that she is unmoved in death, and continues to cruelly reject her own child. The player even has the option to have Raccoon condemn her as a complete monster.

The expectation of deciding between Raccoon choosing to lie to spare his client’s feelings, or tell her the truth, is subverted. The client knows her mother’s cruel response just by Raccoon’s quiet approach; the player cannot alter this.

Afterward Raccoon simply calls his client, “Diamond,” as she asked. It’s a quiet, heartwarming moment, showing that despite Raccoon’s generally depressed attitude throughout the game, they can still care; and it gives this diamond someone who will listen to her wishes and identify her as she chooses.

This moment can end up even more heartwarming if earlier, when Raccoon first met this client, the player chose a dialogue option that says they don’t really understand “this shape stuff”—since later, whether they understand or not, that’s not the point. What matters is that they honor and respect their client’s wishes.

The strange world of The Raccoon Who Lost Their Shape ends up leading to a surprisingly powerful moment when the diamond client explains why she has a bottle of wine made from the corpse of her mother.

She tells Raccoon that the tradition of turning dead shapes into wine is a serious custom for the high-ranking of her society. The wine made from the corpse of a shape is meant to never be opened, to always be preserved.

But in the end, Raccoon finds that she has emptied the bottle of wine that made up the remains of her cruel, dead mother.

A quirky method of worldbuilding resulted in a different way of showing an individual reject a parent for their abusive and prejudiced behavior. It turned the idea of dropping those who hurt you into the startling, quiet image of pouring out a wine bottle. And on a larger level, it was a damning rejection and condemnation of the discrimination plaguing shape society in the game.

Symbolic Shapes

Diamond’s choice is a fitting end to this theme of discrimination in The Raccoon Who Lost Their Shape, as the concept does not truly come up again in the game after this. Shape society’s unjust way of deciding the worth of their people proved to be a large part of the game’s worldbuilding, but it was not the main plot. That ended up being Raccoon’s search for someone they loved, and so the game ends with a conclusion for that.

Yet the themes of discrimination do not feel tacked on. They truly are a part of worldbuilding in the game, making the setting and NPCs come alive with interesting detail. And the themes of discrimination tie into themes of communication and longing, which are felt more in the main plot. For example, though Raccoon’s diamond client faced great discrimination and cruelty, she still longed to communicate with the mother that rejected her because of those prejudiced beliefs.

With its society of sentient shapes ranking themselves by the number of sides they have and other traits, The Raccoon Who Lost Their Shape feels like it could have drawn inspiration from Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, an 1884 novella also about a world of shapes with a strict caste system. (In contrast with the game, Flatland considers a circle to be the perfect shape.)

The Raccoon Who Lost Their Shape was already interesting with its imaginative cast of characters, but the—unfortunately—universal themes of discrimination, and their unique execution in the game’s world, ultimately made for an even stronger and more thoughtful experience.

Latest posts by Alyssa Wejebe (see all)

- From Fan Art to Film Crew: RJ Palmer Talks Detective Pikachu - September 4, 2019

- Women in Gaming: Borderlands 3 Mission Designer Kate Pitstick - August 20, 2019

- Equipping Your Emotions in Crystar - August 14, 2019