It’s dark, you’re alone, and you find yourself walking down a long, dank and dirty hallway. Something is groaning and screaming in another room, so you look for a weapon. In a set of drawers filled with unwashed medical equipment you find a meat cleaver. The wailing is getting louder now, and you hear desperate footsteps, this is it, you’re going to die if you don’t act now. Out of the shadows appears a man wrapped in a straight jacket, his teeth are rotten and he is running straight towards you like you are his prey.

This is a run-down mental health facility, or as the sign says out front, an “insane asylum.”

You tighten your grip on the cleaver and bludgeon the mental patient to death. Finally, you think, you’ve beaten the enemy.

You’ve killed a neurodivergant human being.

How many times have you played through this scenario? I’ve experienced it more times than I can count now, and it’s getting old. Sure, it’s just fiction, and you as the player are not to blame for killing pixels to defend your character, and progress through the game. But when such a large potion of horror games rely on the “mentally ill people are scary” trope, you wonder what it is about mental health that terrifies these game developers so much to keep churning out so many ableist titles. Outlast, Batman: Arkham Asylum, Sanitarium, you know the ones.

The Big Bad

Mental illness has been the big bad in video games for decades now, however there are a few mental health focused horror games that don’t give in to damaging stereotypes. So with this in mind, I wonder; in ten years time, will mental health still be the villain in the video games industry? Or will we see more mentally ill characters as the hero, rather than the enemy?

One of the reasons why it’s so offensive to paint mentally ill folk with this brush is because it’s such a motivational cop out for evilness. Games like Outlast imply that mentally ill people cannot control their actions, and that we are inherently and outwardly violent. When actually, if violence does come into the mix, then mentally ill folk are more likely to hurt themselves than others around them. Even then, only around 3-5% of neurodivergant people commit violent crimes each year. In fact, they’re ten times more likely to be the victims of said crimes, done by neurotypical people.

It’s a lazy trope too, which makes it all the more irritating because instead of coming up with a thought provoking backstory for their motivation, developers flippantly label the villain “insane” and leave it at that. Yet there are so many routes you could take while writing why your villain is evil; for financial gain, the thirst for corporate power, for political control, revenge, the possibilities are endless.

And hey, “insanity” is a real excuse for real life violence too, so that makes it all the more awkward.

The Seed of Fear

Yes I know that the many enemies of these games aren’t based on me, a woman with mild depression and moderate OCD, and moderate to severe anxiety. They’re based on the patients in actual mental hospitals that were declared unfit for independent living. They’re based on the patients with psychotic disorders that cause them to scream at hallucinations, and are unable to consciously control their limbs. But how in the world does this make the trope any better? It doesn’t, it’s worse. Yes mental health can become erratic, but when you stereotype psychiatric patients and turn them into monsters via fiction, you plant the seed of fear and bigotry in the next generation who plays the game. Because yes, people do use what they’ve learned in fiction in real life.

It tells us that the scariest thing these devs can imagine is being mentally ill, and that makes people like me, and people with more severe symptoms, feel ostracized.

But let’s focus on the positives for a moment; the games that don’t use this trope, and actually show some sort of understanding of neurodivergance. Most of (what I consider) progressive horror games, come mainly from the indie games industry, which isn’t surprising since it’s clear that ableism in games sells way too much for triple A dev teams to give up on.

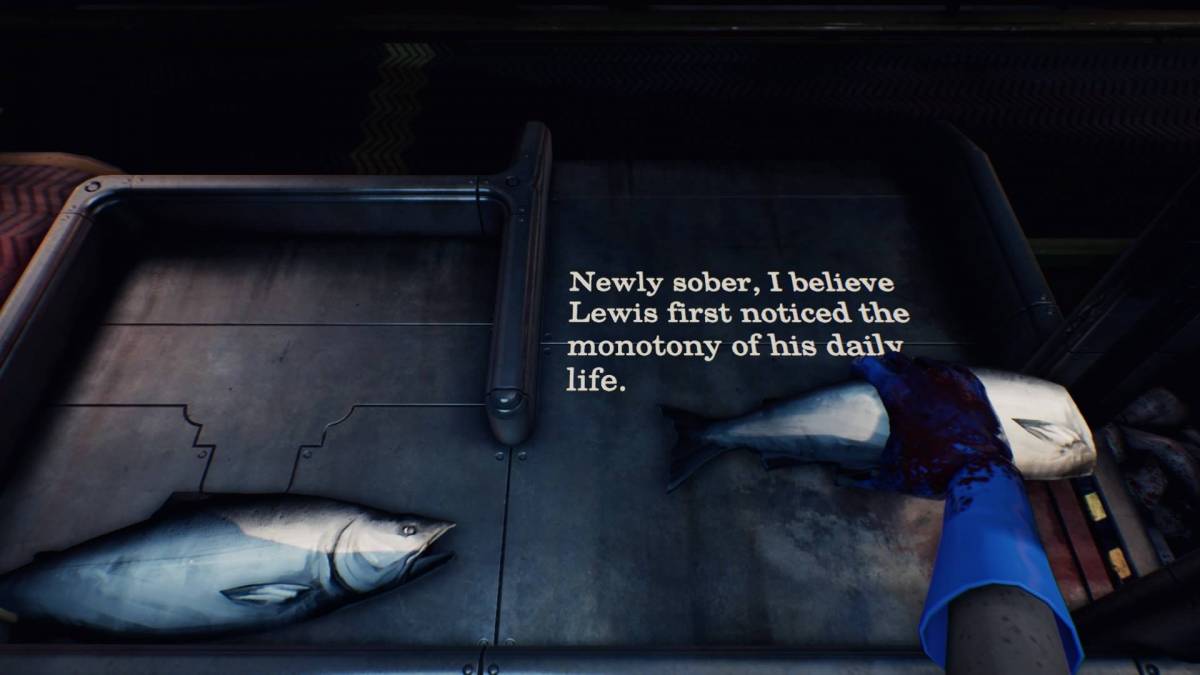

What Remains of Edith Finch, is an example of a game that doesn’t use mental illness for shock factor, yet still manages to hold a thrilling and unsettling story line. Though not horror in the traditional BOO! sense, Edith Finch explores the idea of death in it’s most simple and realistic terms. Many of the late characters in Finch’s family tree are clearly neurodivergant, including her brother Lewis of whom suffered from depression, dissociation, dellusions, and suicidal feelings. These symptoms however are not played for spooks. The unsettling and the sad thing about this segment, is not the big scary illness coming for the character, but the fact that those around him did not notice that he was detaching himself from reality. No one helped him, no one in his workplace thought to shake up his duties in order to make him more comfortable, he was ignored.

Similarly, Elude is another game that doesn’t blame or vilify the neurodivergant character. Elude, just like Depression Quest, is a game that visually discusses the impact of clinical depression, and the difficult road to recovery. The game play of Elude is interesting because you’re not really fighting metaphorical “depression,” demons, but you are physically walking your character from the dark depths of the forest (depressive episodes) to the bright and happy plains of the sky (recovery, and passion for things you love). Depression in this context is seen as something to move away from, rather than a catalyst for violence and evilness.

This is what separates games like these from a game like Sanitarium; who the big bad is. Does it blame the neurodivergant person for their illness? Does it make them out to be a creature that needs put down? Does it make a fun and spooky activity out of their pain? If so, it’s ableist. Conversely, does it make you feel empathy for the character? Does it add to the emotion of the story? These are the questions devs have to ask themselves before they create a storyline around mental health, and this is how you make a great plot line.

Respecting the Player

The problem is, there just aren’t nearly as many of these games as there should be, even though there are plenty I’ve missed out, so it’ll be a while till the ableism dies down, in my opinion.

Making the events of real people’s lives into a fun romp, is as disrespectful as it comes. When you attack zombies or robots, it doesn’t matter so much because these things don’t exist in real life (well, robots do exist but not killer ones…I hope). But when you attack a psychotic patient because they are “crazy” this leaks over into real life way too easily. When you talk about how terrifying the “sch*zo” enemies are to your friend, who has said disorder, you alienate them. You essentially turn into the so called hero attacking the mental patient, just without a game pad.

If neurodivergant folk had more representation in games then it wouldn’t be as big as an issue; if in the same game you had a mentally ill protagonist that just happened to be mentally ill, then it wouldn’t be as weird. It’s the fact that mental illness is mostly only brought up as a scary trope, that tells us that most developers see neurodivergance in a negative light.

We’re not even token characters to them, we’re their worst nightmares…in pixel form.

Latest posts by Stephanie Watson (see all)

- New Normative Comment Clinic: Don’t Worry N4G, We’re Here to Help - February 23, 2018

- Butterfly Soup: The Bisexual Visual Novel We’ve Been Waiting For - January 4, 2018

- Is There a Link Between Intelligence and Playing Video Games? - December 6, 2017