There’s a heavy, acrid quality to the air in Karnaca tonight. I can’t feel it, of course; there’s a controller, a screen and a universe of suspended disbelief between us, but I can feel it. The fading sunset wavers on the edge of the horizon, leaking out crimsons and ochre and silvers along the surface of the water like a drowning painter’s palette, or like a bleeding corpse reduced to fish food.

I didn’t come to this waterfront palace to admire the scenery tonight; I came here to kill. Between me and my target Duke Luca Abel, the opulent and sadistic political leader of Serkonos, is a regiment of armed guards. Women and men, with swords and pistols and the military training to use them, each prepared to sacrifice their lives in service of their employer. If I cared to think about it, I might come to the realisation that each of them has a story just as complex as my own; just as filled with betrayal and heartbreak and laughter and smashed odds. But if I’m to remain faceless, my humanity obscured by the grotesque metal mask that hides my identity as the Most Wanted man in Karnaca, then they must remain faceless too. If some hint of compassion slips through this mephistophelian guise of mine, then my facade slips away with it . And if that goes – if I recognise the mutual humanity I share with each of these people, and realise that it’s only circumstance that has made us adversaries – there’s a chance my blade might falter. And here, that could mean death. . .

Well, game over, at least. Luckily, Dishonored 2 has made things pretty simple for me. There’s nothing as immersion jarring as a score counter here – kills aren’t worth points, exactly – but there’s enough reasons to write off each act of murder as mere mechanical necessity. Most of the guards carry bullets. A grenade maybe. A cream coloured belt purse, conveniently expressing, in precise numerical value, exactly how much their life is worth. Some wear red, some are in blue. Standard videogame hierarchy colour codes. The blues are legion; disposable grunts, cannon fodder, rat feed. The reds might put up a bit more of a struggle, but they go down just as easy from a knife in the back, and leave better pick-ups behind. Whatever else they leave behind – a job, a dream, a family – is none of my concern. I don’t need to know. Unless, of course, I want to. Because if I do feel like learning about these people, the Dishonored series will let me. All I need to do is show a little heart.

More than meets the crossshairs…

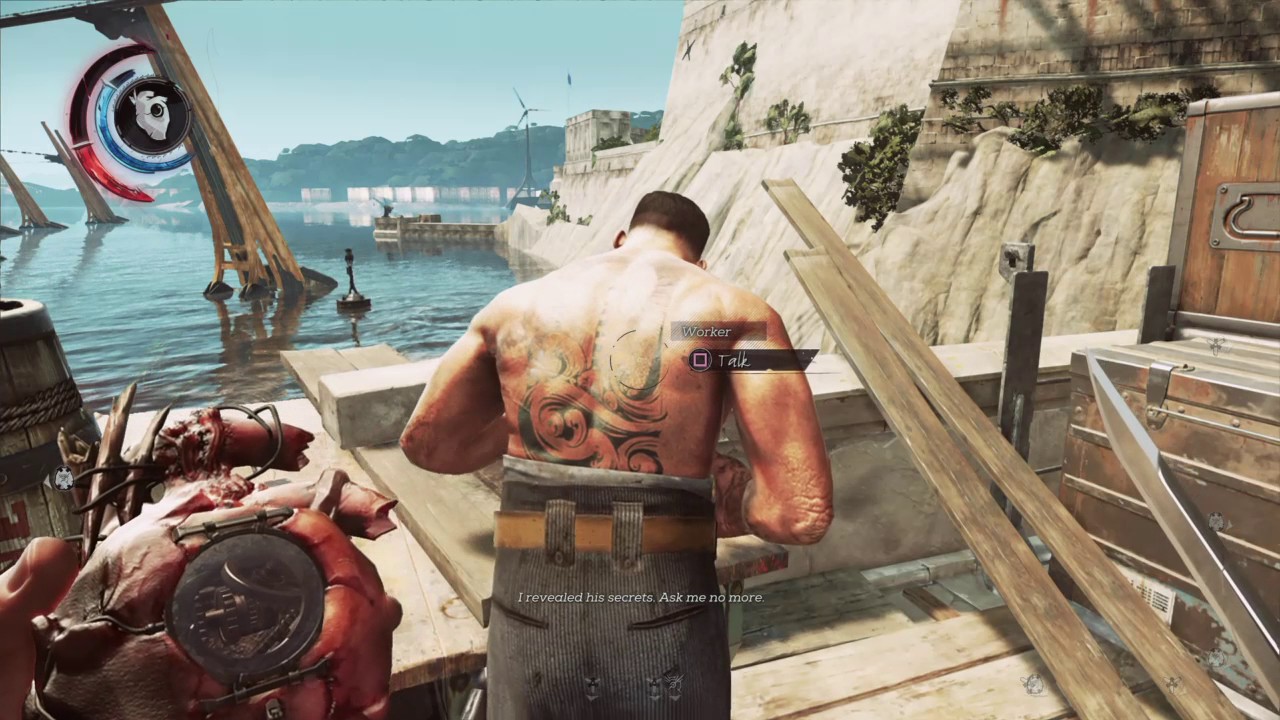

It’s quite a big heart, actually, because it belonged to one of the only big-hearted characters in Dishonored, Empress Jessamine Kaldwin – lover and mother to Dishonored 2 protagonists Corvo and Emily, respectively. It doubles as an eminently game-y collectible power up radar, but that’s the less interesting of its two functions. If I point the heart at any of the games NPC’s, as a popup menu tells me, the heart will whisper secrets. Clandestine murders, acts of betrayal, abused power, sure. But also tales of alcoholism, of broken homes, of families and lovers and private dreams. And just like that, I’m no longer surrounded by obstacles, but by characters.

It’s quite a big heart, actually, because it belonged to one of the only big-hearted characters in Dishonored, Empress Jessamine Kaldwin – lover and mother to Dishonored 2 protagonists Corvo and Emily, respectively. It doubles as an eminently game-y collectible power up radar, but that’s the less interesting of its two functions. If I point the heart at any of the games NPC’s, as a popup menu tells me, the heart will whisper secrets. Clandestine murders, acts of betrayal, abused power, sure. But also tales of alcoholism, of broken homes, of families and lovers and private dreams. And just like that, I’m no longer surrounded by obstacles, but by characters.

The void between the words

In the fantastic video essay ‘The Metaphysics of Narrative Structure’, Brian Artese suggests the idea of a silent contract between reader and text, upon which the two agree that any mysteries in the story are known, on some level, by its creator. A novel might never specify exactly what the villain ate for breakfast that morning, for example, but somewhere inside the imagination space of the fiction, this information does exist. Artese is drawing on the ideas of narratologist Gerard Genette, who described the essence of intrigue as the author withholding some of ‘all that he knows’. The reader might never find answers to every question they have about the fictional world they’re exploring, but the suggestion that, on some level, this information exists, is enough to draw the reader in; to make the mystery worth exploring. Dishonored‘s heart is Genette’s contract, but it’s more than that, too. Like the contract, a few times using the heart lets me know that every one of these previously faceless enemies have their own motivation; that potential questions about their lives were given consideration. They’re more than enemies – they’re individuals, and they’ve probably all got sore feet from walking the exact same patrol route for hours. Like David Foster-Wallace’s ‘This is Water‘ speech, it’s an invitation to re-examine the agency of those who share this environment, a reminder that each one has a story. What’s truly special about the heart, though, is the way these micro-narratives feed into the themes of Dishonored‘s fiction.

Dishonored‘s heart is Genette’s contract, but it’s more than that, too. Like the contract, a few times using the heart lets me know that every one of these previously faceless enemies have their own motivation; that potential questions about their lives were given consideration. They’re more than enemies – they’re individuals, and they’ve probably all got sore feet from walking the exact same patrol route for hours. Like David Foster-Wallace’s ‘This is Water‘ speech, it’s an invitation to re-examine the agency of those who share this environment, a reminder that each one has a story. What’s truly special about the heart, though, is the way these micro-narratives feed into the themes of Dishonored‘s fiction.

Mechanics as Metaphor

The world of Dishonored, like the 19th century London it take inspiration from, is elitist and nepotistic. It’s what Marx would have called Bourgeois, what Foucault might have described as nonegalitarian. It’s full of wankers, basically. Anyone without status or wealth is inconsequential and disposable, a footnote to the biographies of the powerful. It’s a level of elitism and dehumanisation that I doubt many would be comfortable with if experienced in the real world. But in so many games, we don’t only ignore this kind of exceptionalism – we actively embrace it. The ‘great man‘ theory, an idea made popular by 19th century Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle, reframes the past as a series of acts and decisions by influential individuals. “The history of the world is but the biography of great men”, says Carlyle, conveniently forgetting that, for much of western history, none but the dominant hierarchy (i.e old rich white dudes) had the resources or the social status to be allowed ‘greatness’ to begin with. At best, it’s a highly reductive, narrowly focused view of how the world is shaped. At worst, it reads like Nietzsche’s ideas on the Übermensch as viewed through the exceptionalism-muddied lenses of the Third Reich. But this narrative of heroic superiority runs deep in cultural storytelling. The tendency to objectify secondary characters to the level of picayune mannequins bearing helpful trinkets, or to portray human obstacles to heroic success as drenched in unambiguous otherness, limits the ability of fictional worlds to say anything worthwhile, or even believable, about our lives.

The ‘great man‘ theory, an idea made popular by 19th century Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle, reframes the past as a series of acts and decisions by influential individuals. “The history of the world is but the biography of great men”, says Carlyle, conveniently forgetting that, for much of western history, none but the dominant hierarchy (i.e old rich white dudes) had the resources or the social status to be allowed ‘greatness’ to begin with. At best, it’s a highly reductive, narrowly focused view of how the world is shaped. At worst, it reads like Nietzsche’s ideas on the Übermensch as viewed through the exceptionalism-muddied lenses of the Third Reich. But this narrative of heroic superiority runs deep in cultural storytelling. The tendency to objectify secondary characters to the level of picayune mannequins bearing helpful trinkets, or to portray human obstacles to heroic success as drenched in unambiguous otherness, limits the ability of fictional worlds to say anything worthwhile, or even believable, about our lives.

Dishonored‘s heart doesn’t completely remedy this tendency. It’s partly a function of narrative structure, partly just practical for games to focus on only a few characters. Each title in the series tells a story which, at its core, is still about one or two righteous protagonists overcoming an opposing power to assert their own. But along with an extensive lore and deft thematic brush strokes that paint the portraits of the powerful with despotic sneers on their hideously caricatured mugs, it does add a layer of satire and commentary on the sort of story that writes off the daily struggles of the many as incidental to the grander triumphs of the few. It asks if the death of an empress is really that great of an injustice while others have difficulty finding bread. It asks whether the faceless hordes of enemies we’re used to mowing down in this sort of game might have stories just as worth telling as our own. It asks whether our own tendencies to assume that inhabiting the viewpoint of a character is a sure sign of heroism are inherently flawed. It re-frames our characters presence in the narrative space as a potential invader, rather than the crux that the story revolves around, and it does it all while making a lot of other game’s stories look half-hearted in the process.

Nic Reuben

Latest posts by Nic Reuben (see all)

- These Horizon Zero Dawn Photographers Find the Soul in the Machines - March 16, 2018

- A Completely Objective Review of An Apolitical Game - February 9, 2018

- This Horizon Zero Dawn Photographer Brings the Post Apocalypse to Life - January 17, 2018